The Shapes of Stories, Part IIb: When the World Refuses You

What happens when the story wasn’t written with you in mind?

Throughout my limited series The Shapes of Stories, we’ve been exploring the idea that the stories we tell about our lives don’t just help us make sense of experience, they actually shape it. The narrative forms we rely on carry cultural expectations: what growth should look like, what healing should produce, which lives are worth narrating in the first place.

But when our actual experiences don’t align with those templates—when the meaning doesn’t come, or the transformation never arrives—the dissonance can be profound. In Part I, we looked at the redemptive arc we instinctively reach for: the promise of meaning through suffering, of coherence through struggle.

It’s a powerful shape, but also a limiting one. Last week, in Part IIa, we considered what happens when healing never comes or the lesson never arrives. This rupture in the narrative often results in confusion, guilt, or silence.

But there’s another kind of rupture, one that doesn’t arise from within the story, but from outside it. Sometimes we come to see the story we’ve been living, and we walk away.

When You Refuse the Story

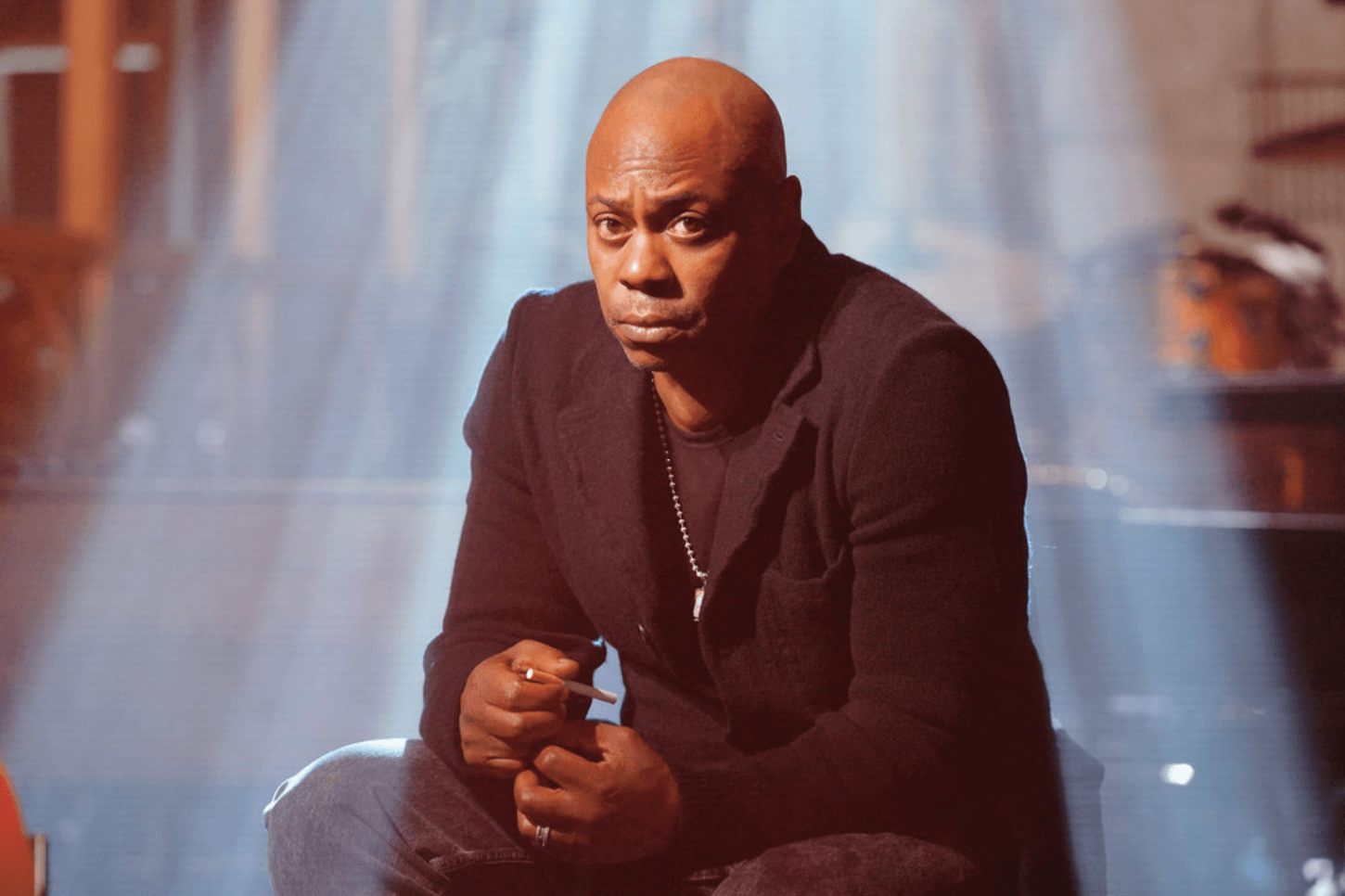

Dave Chappelle had made it. Born in Washington, D.C. and raised between there and Yellow Springs, Ohio, Chappelle began performing stand-up comedy as a teenager, eventually moving to New York City, where he quickly gained a reputation for his sharp wit and fearlessness, often tackling controversial topics such as race, class, and power through his comedy.

By the mid-1990s, he had become a recognizable actor, landing supporting roles in films like Robin Hood: Men in Tights and The Nutty Professor, and had something of a breakthrough when he co-wrote and starred in the 1998 cult comedy Half Baked. But despite steady work, he remained on the margins of mainstream recognition—a gifted comedian waiting for the right platform.

That moment came in 2003, when Comedy Central greenlit Chappelle’s Show, a sketch comedy series co-created with writer and producer Neal Brennan. The network took a gamble on Chappelle’s unfiltered perspective and distinctive voice—and the show quickly became a breakout hit.

By 2005, Chappelle’s Show had become one of the most popular and influential programs on television. Airing on Comedy Central, the show was hailed for its unflinching satire of race, class, gender, and pop culture. Chappelle himself was celebrated as a genius—brilliant, subversive, uncompromising. The sketches went viral before that term was…well, viral (my favorites were “The Racial Draft” and the Clayton Bigsby sketch, which focuses on a blind white supremacist who doesn’t know that he’s black).

Chappelle had developed the kind of cultural capital that transcended comedy. People quoted him, gathered to watch new episodes, hung on his every word. The network offered him a $50 million contract to continue the show.

And then, at the very height of his success, Chappelle walked away. In the middle of filming the third season of Chappelle’s Show, he abruptly left the set, gathered his family, and disappeared to South Africa without notifying the network, his co-creator, or the press. For weeks, no one knew where he was. Rumors swirled—mental breakdown, drug relapse, creative burnout. When he returned, he explained that something had shifted. He saw how his work was being consumed—how sketches meant to critique racism were being misread as permission to laugh at it. A moment on set, when a white crew member laughed “the wrong way,” stuck with him. “It was the first time I felt like I was doing something that was socially irresponsible,” he later said.

His departure confused many, even angered some. Why would anyone walk away from $50 million? From fame? From the very narrative he’d worked so hard to build? The answer, as Chappelle made clear, was simple: because it no longer felt like his.

And for this refusal, Chappelle paid a price. In the years that followed, he was mocked, pathologized, and dismissed. Media outlets speculated about his mental health. Industry insiders questioned his reliability and arrogance. For some, he went from genius to cautionary tale overnight—not because he failed, but because he refused to continue performing the role assigned to him. The narrative he was being asked to fulfill (“grateful Black comic climbs the ladder and becomes crossover star”) no longer aligned with who he wanted to be.

So he rewrote the ending. And, in a culture that equates visibility with value, his disappearance felt like a breach of contract—not just with the network, but with the public.

Side note - if you aren’t familiar with Chappelle’s work and are curious about what he’s doing these days, I recommend his Netflix special 8:46, which isn’t exactly comedy, but still one of the most powerful, infuriating, and thought-provoking performances I’ve ever seen.

Refusing the script isn’t always a declaration. Sometimes it’s simply an escape—a decision made not in defiance, but in self-preservation. Chappelle’s exit unsettled people because it broke the spell of a familiar narrative: that success, once achieved, should be embraced without question, that fame and fortune are proof of fulfillment.

I’d argue that the confusion and hostility Chappelle provoked came from something deeper: the unsettling realization of just how little space our dominant narratives make for doubt, ambiguity, or moral conflict. He disrupted the payoff we were expecting—the rise, the reward, the closure—and reminded us that choosing not to perform a story can be as meaningful as completing one. In that choice, we catch a glimpse of something radical: a refusal not just to reject the story, but to reclaim the self beneath it.

As the French philosopher Michel Foucault argued, power doesn’t merely constrain—it shapes. It works not just by limiting behavior, but by defining what kinds of lives are imaginable in the first place. It does this, he explained, by producing norms: ideas about what’s acceptable, legible, admirable. Power defines what success looks like, what healing should feel like, what stories are worth telling—and how those stories must end. “Power,” he wrote, “produces reality; it produces domains of objects and rituals of truth.” In this sense, the scripts we’re handed—whether in pop culture or personal life—don’t simply reflect who we are. They help form who we’re allowed to become. To reject the dominant narrative, then, isn’t just to walk away from a role. It’s to step outside a system that tells you what kind of person you must be in order to be recognized. That kind of refusal is risky. It costs visibility. It invites misunderstanding. But it also opens a door—to a different kind of authorship.

And yet, not everyone gets to walk away.

When the World Refuses You

Not all refusals are voluntary. Sometimes, the world refuses you.

The theorist Judith Butler writes about legibility—the idea that identity must be made culturally “readable” in order to be recognized. To be accepted, a person must conform to familiar norms of race, gender, sexuality, nationality, ability. They must make sense. This tendency doesn’t just shape how people are perceived, it determines whose lives are grievable, whose pain is credible, whose stories are allowed to circulate. “The unintelligible,” Butler writes, “is unlivable.” To fall outside the frame of what’s understandable is to risk erasure. Or worse.

This phenomenon is especially true in public life, where identity is often reduced to symbolism, and success is permitted only within certain narrative boundaries. Step too far outside the script, and you become a threat—not because of what you’ve done, but because of what your existence disrupts.

Consider the figure of the “good immigrant.” The story is familiar: arrive humbly, work hard, stay quiet, show gratitude. Assimilate. Succeed. It’s a story we like to hear because it confirms our national myths. It reassures us that the system works. And it’s enforced not only through policy, but through media narratives, political rhetoric, and the emotional expectations of the audience.

Ilhan Omar, a Black, Muslim, former refugee, represents exactly the kind of success story this narrative is supposed to affirm. She came to the United States from Somalia as a child, grew up in public housing, and became one of the first Muslim women elected to Congress. Her life should have been celebrated as proof of the American promise.

But many people think Omar isn’t a “good immigrant” because she doesn’t demonstrate enough gratitude or deference. She doesn’t sublimate herself to those in traditional positions of power, but instead challenges them. She doesn’t thank the system for letting her in, but instead critiques the system, calling out U.S. foreign policy, systemic racism, and Islamophobia. She questions the terms of belonging, the invisible contract that every person who represents “difference” is expected to follow.

And for that, she has been labeled ungrateful, even dangerous. She became a target of relentless harassment, death threats, and public suspicion—not for what she has done, but for who she refuses to pretend to be.

The same has been true for Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Rashida Tlaib. Their success should have made them legible: firsts, groundbreakers, symbols of progress. But their refusal to be compliant or quiet—to temper their critique, soften their tone, shrink their ambitions—has rendered them disruptive, what we might call “illegible” in Butler’s terms. The dominant narrative for those who are “different” and then admitted a seat at the table demands assimilation. They have rejected that narrative.

These women are not failures of the story. They are threats to its simplicity. And that, perhaps, is the clearest sign that the story was never written with them in mind.

This demand for legibility extends across public life—not just in politics, but in entertainment, media, and celebrity culture. The dynamic plays out across industries. Public women—especially those who disrupt familiar archetypes—are punished not just for breaking the script, but for refusing to perform at all. Janet Jackson was blacklisted after the 2004 Super Bowl incident, while her white male counterpart walked away unscathed. Sinéad O’Connor was vilified and ostracized for tearing up a photo of the Pope on SNL—an act of protest decades ahead of public opinion. Britney Spears, whose public breakdown disrupted the “pop princess” narrative, was placed under a conservatorship that stripped her of legal agency for over a decade. In each case, the script was clear: be grateful, be appealing, be legible. And when they refused—or simply failed to perform the role—they were punished, pathologized, or erased.

Conclusion: A Different Kind of Story

We reach for stories because we need them. To remain psychologically healthy, we need to connect effects to causes, because it simply isn’t sustainable to exist in a world devoid of meaning, where the things that happen to us are random, without purpose or consequence. Therefore, we shape our lives into familiar, comforting arcs.

But the stories we have to choose from aren’t always sufficient. Sometimes there’s a rupture—an illness, an injustice, a refusal—and we begin to wonder if the arc we’re following was ever really meant for us.

Part II of The Shapes of Stories has traced three kinds of narrative dissonance: when the arc fails to deliver meaning, when we choose to abandon it, and when the world refuses to let us tell it at all. In each case, what’s at stake isn’t just coherence. It’s survival. Legibility. Belonging.

But rupture can also create possibility. When the old shapes collapse, we can begin to imagine new ones, not cleaner or more resolved, but more honest. Stories that allow for ambiguity. For repetition. For unfinished endings. For people who do not heal on cue, and who do not exist to inspire.

We don’t need better stories so we can become better protagonists.

We need better stories so we can stop punishing ourselves—and each other—for breaking the ones we were never meant to fit.

Because in the end, a life is not a lesson. It’s not a plot.

It’s a person.

And while refusal can be radical, it isn’t enough. At some point, we still have to live, still have to speak, still have to find language that feels like our own.

If we can’t rely on inherited stories to hold us, then we face the harder, quieter task of building new ones—not cleaner, but truer.